In March 2022, the Queen’s Nursing Institute Scotland conducted an online survey about Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD). This was a Year 1 activity of Healthier Pregnancies, Better Lives (HPBL) – a QNIS programme supported by Cattanach and The National Lottery Community Fund. All community nurses and midwives anywhere in Scotland were eligible to participate in this survey.

Dr Jonathan Sher

Lisa Lyte

Prof Moira Plant

This is the third in a series of blogs reporting on what we learned from the Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) survey, completed by a cross-section of Scotland’s community nurses and midwives. The first blog available here provided an overview, whilst the second available here focused on ‘speaking about drinking’ with the patients/clients in their practices.

The next section of this QNIS/HPBL questionnaire focused on nurses’ and midwives’ own encounters (or, as it turned out, their perceived lack of encounters) with people affected by FASD. The Scottish Government estimates that approximately 172,000 children, young people and adults are directly affected by FASD. That means that, in our relatively small nation, a large number of people have this lifelong neurodevelopmental condition.

We discovered that 3/4 of the survey respondents had at least a decade of experience across more than 20 specialties of community nursing and/or midwifery. Given the government statistics, this diverse and experienced group of nurses and midwives are likely to have worked with many FASD affected people over the years, across many different roles and settings throughout Scotland. And yet, more than 70% of respondents indicated they had ‘rarely’ or ‘never’ dealt with anyone they even suspected of having this neurodevelopmental condition. Less than 10% of respondents said they encountered such a person on a daily or weekly basis. Of the 30% who suspected the possibility of FASD, the most common reasons cited were:

- behavioural/developmental concerns

- known family history of alcohol misuse

- observable difficulties with thinking/concentration

- distinctive facial features

The majority did not consider that they could be dealing with an FASD-affected child, young person or adult; and therefore, took no action to refer, diagnose or respond with FASD in mind.

When respondents, either with or without experience of FASD, were asked what they did (or would do) if they suspected the possibility of FASD, the most common answers were:

- raise it with a colleague – 80%

- make a mental note of it – 72%

- make a formal FASD referral – 50% (of those with experience)

- conduct a formal assessment – 20%

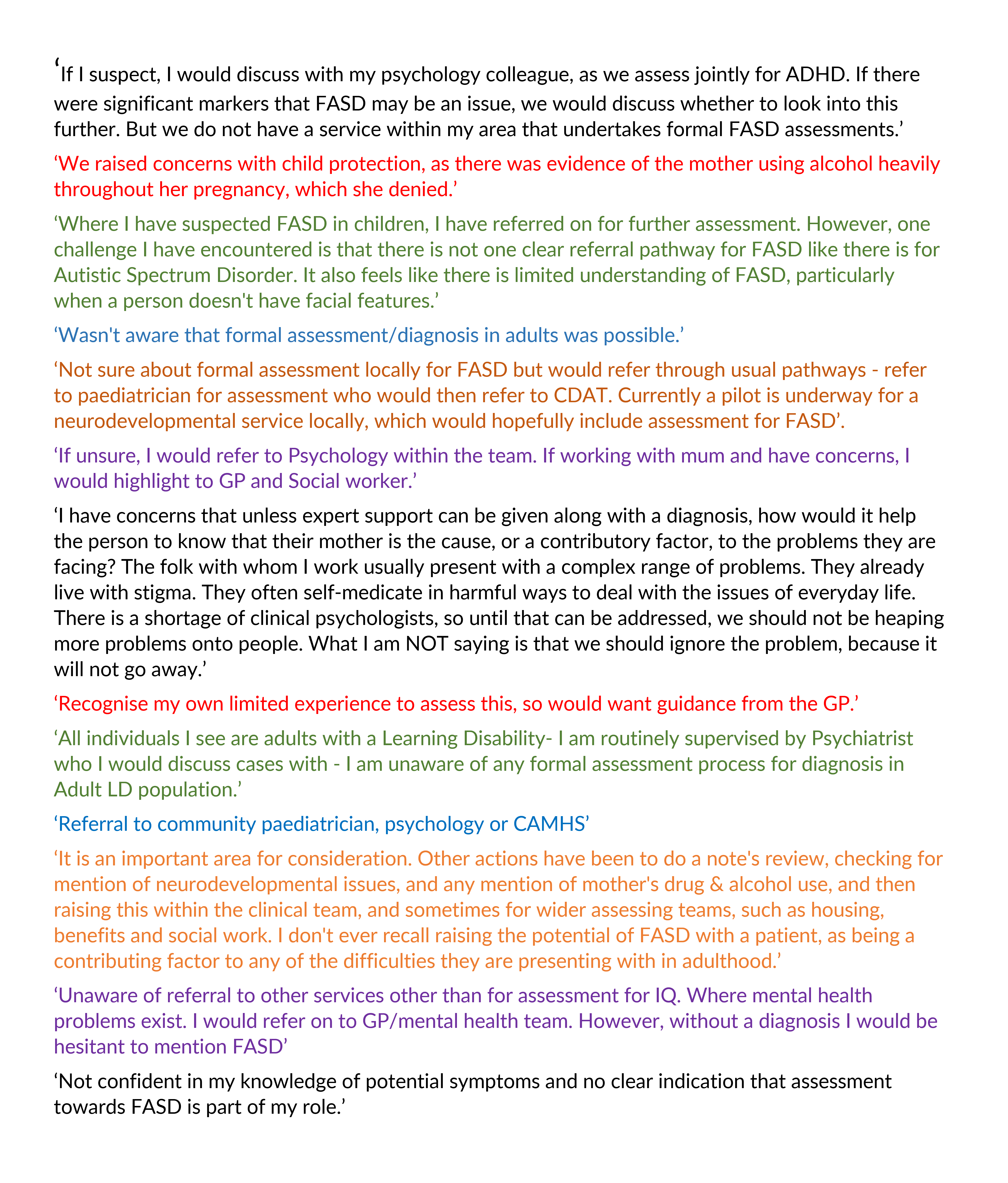

The following quotes reflect their wide-ranging comments, perspectives and experiences:

It is telling that 42% of respondents noted they had never encountered a person they knew was affected by FASD, often because an official diagnosis was not part of that person’s medical record. On average, these professionals have been employed for well over a decade and represent an ‘illustrative sample’ of community nurses and midwives here.

Of the 58% who knew of a person in their practice with an FASD diagnosis, the most frequently cited number of cases – by a large margin – was just one. Only 19 of the 219 survey respondents have encountered five or more people with recognised FASD diagnoses in their careers. There were a handful of participating nurses and midwives who knew of many (20+ cases). One participant indicated having encountered between 80 and 100 affected individuals over their career.

This questionnaire revealed the extent to which FASD has been invisible across communities and nursing specialisms These figures would never have led to an estimate of 172,000 children, young people and adults affected by FASD across Scotland. Why does such a chasm exist between the government figures and our findings?

Community nurses and midwives are dedicated, highly skilled professionals who often have close relationships with the patients/clients in their person-centred practices. Yet, even in this group, FASD has remained invisible.

Other research and international evidence offer some insights. One is that Scotland has long been considered to have a drinking culture that promotes an ‘unhealthy relationship with alcohol’. Another is that FASD is often misunderstood or misdiagnosed as other neurodevelopmental conditions, such as ADHD. This becomes even more complicated when understanding that these conditions are often co-morbidities with some overlapping symptoms. An even simpler explanation is that FASD has been largely absent in the initial education, training and continuing professional development of Scotland’s relevant workforce in the health, education, social work and justice systems.

The good news is that FASD is steadily becoming more visible and isn’t the blind spot it once was. History does not have to become destiny. The best news is that Scotland’s community nurses and midwives are extraordinarily – perhaps uniquely – well-placed to play a leading role in FASD prevention, awareness-raising and effective assistance/support.

The final blog in this series explores the next steps the respondents are now ready to take.

This is the third blog in a series of four, you can read the other blogs here:

- FASD is becoming more of a concern for community nurses and midwives (qnis.org.uk)

- Speaking About Drinking (qnis.org.uk)

- What Invisibility Looks like (you’re here)

- Spotlighting a Blind Spot (qnis.org.uk)