Professor Flora Douglas

Professor of Public Health, School of Nursing, Midwifery and Paramedic Practice

Robert Gordon University

Professor Flora Douglas

In 2021, I was both privileged and humbled to lead a qualitative research study that involved interviewing parents, health visitors, community midwives, and family nurse practitioners about their experiences of both enacting, and benefiting from, the so-called Financial Inclusion Pathway (FIP). The FIP is designed as one of several strategies that operate within Local Child Poverty Action Plans which all Scottish territorial health boards are required to produce and act on in collaboration with their respective local authorities. The FIP aims, through routine health professional enquiry, to identify families with children under five who are experiencing financial hardship and offer onward referral for financial advice and support to help increase their household incomes. Our study aimed to find out how NHS Grampian’s FIP was working in practice, and in this blog, I offer my reflections on its key learning points.

First, and to put our findings into context, we know that child poverty rates are increasing again due to rising energy, food, and other essentials costs [1]. One in four UK households with children is now considered to be living with food insecurity with the poorest 20% of UK households having to spend almost half of their household income on food to meet current Government dietary recommendations [2]. Lone-parent families in particular are experiencing unprecedented levels of poverty and economic distress in the UK [8] and are increasingly seeking help from food banks to feed their families [2]. Food banks themselves are struggling to meet current demands and are concerned they will have to cut back the level of support they currently offer due to the cost-of-living crisis too [3].

DOUGLAS 2022 Midwives health visitors (REPORT)

In Scotland, pregnant women and families with a child under 3 who are on a low income are eligible for Best Start Foods. Families may also be able to receive Scottish Child Payment for eligible children under 16, as well as the three Best Start Grants. Together, these payments could be worth around £10,000 to those qualifying households by the time a family’s first child turns six years old, and around £9,700 for subsequent children.”. However, the value of those benefits has declined in real terms due to recent price rises on food and fuel [1, 4]. In the middle of this, families with infants are struggling to access infant formula. Rising retail costs have made formula prohibitively expensive for some and, for those families in food crisis, some food charities may not be able to stock or supply formula due to different ideas about what the UNICEF Baby Friendly Initiative guidelines permit them to do or not do [5].

When we collected our data in 2021, before the current cost of living crisis, our parent interviewees were clearly struggling to put food on the table and pay their bills, in the context of their struggling to manage insufficient income alongside imposed commitments to paying back government debt. This finding leads me to (re)argue that income-driven maternal and infant food insecurity remains poorly recognised and underestimated within public policy, practice, and research in the UK, and this needs to change [6].

Strikingly, although parents appreciated the FIP concept as something that could help reduce stigma and improve access to benefits support, the study also highlighted barriers that can prevent parents from disclosing money worries to health professionals [7]. These barriers include concerns that their parenting abilities will be brought into question, fears about potential child protection processes, and exacerbation of partner abuse relating to financial control and coercion. At the same time, our health professional interviewees indicated they were sensitised to these concerns (which inhibited some from raising the issue with all parents) and felt deeply affected when they could not secure the necessary resources to help families facing extreme financial hardship.

DOUGLAS 2022 Midwives health visitors (REPORT)

They were also very concerned too for those ‘newly poor’ parents who might never have had to claim government benefits in the past, and who might be unaware or unwilling to claim those benefits or admit to a health professional they were struggling with money worries. The study suggested that being unable to provide adequate support exposed practitioners to moral distress, increasing their risk of experiencing secondary trauma.

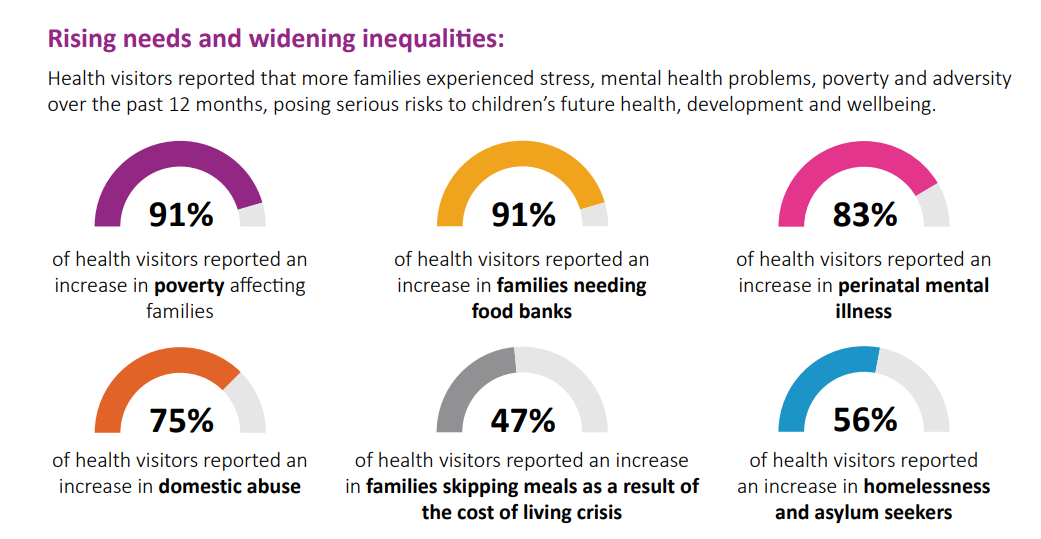

The Institute of Health Visiting (iHV) recently released its annual health visiting survey report State of Health Visiting in the UK. The results of this survey mirror the narratives established in the qualitative work I conducted around the FIP. It has become increasingly difficult for families to get access to resources and support for social and economic issues. Both studies have found that health visitors, midwives, and family partnership nurses are reporting rising needs, expanding caseloads, and increased moral distress. Substantial effort is required to address these profound issues and health professionals, whilst they have the inclination, do not have the time.

Institute of Health Visiting, State of Health Visiting Report 2022

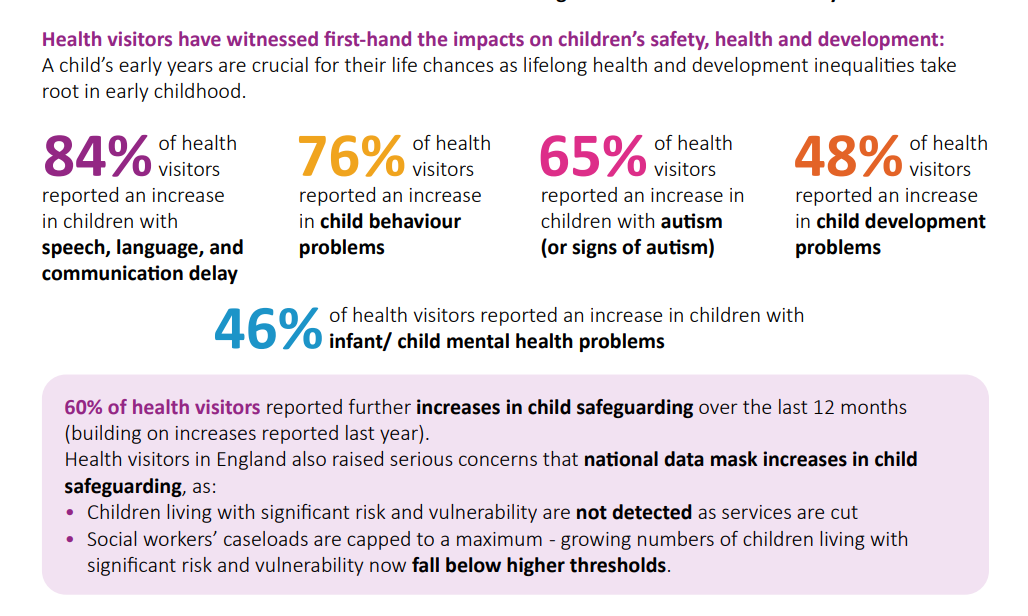

Health visitors, midwives, and family nurse practitioners see first-hand the negative impacts of economic and social policies that undermine the health and wellbeing of the people they care for. The statistics provided by the Institute of Health Visiting in their State of Health Visiting Report support this observation. However, it should be noted that this is an anonymous survey. During my research, some study informants voiced concerns about appearing to be ‘too political’ when discussing those observations during their interviews. I believe that community-based nursing and midwifery professionals are uniquely placed to articulate these kinds of concerns and have professional legitimacy to talk about their observations from practice, influence policymakers, encourage better decisions and ultimately benefit the people and families they care for.

Institute of Health Visiting, State of Health Visiting Report 2022

Therefore, I believe community nurses, midwives, and health visitors working with vulnerable families have an important role to play in advocating for:

- The right to a decent living through adequate levels of social support that reflects the true costs of living needed to raise a family in the UK,

- The right to food (or in the case of infants – the right to be fed)- means that governments ensure that they have sufficient income to be able to buy food for themselves.

Clare Cable (QNIS) and I have been in conversation, and we are keen to bring together a group of interested professionals to explore these issues. We would like to hear your stories of supporting individuals, families, and communities at this time and to consider ways in which the voices of nurses, midwives, and health visitors might be used to advocate for social justice.

If you would like to be involved, then please email Janet McArthur to say, ‘count me in!’ with Maternal and infant food insecurity in the title line and your preferred contact details: janet.mcarthur@qnis.org.uk

Further reading

- More information on Best Start Grant and Best Start Foods (mygov.scot)

- More information on Scottish Child Payment (mygov.scot)

References

- Stone J & Hirsch D. The Cost of a Child. 2022. Child Poverty Action Group. Available from: Cost_of_a_child_2022.pdf (cpag.org.uk)

- Food Foundation [Internet] Food Insecurity Tracking. 2022: Available from: Food Insecurity Tracking | Food Foundation

- Goodwin S. Ending the food bank paradox. BMJ. 2022 Dec 2;379.

- Statham R, Smith C, Parkes H. Tackling child poverty and destitution: Next steps for the Scottish child payment and Scottish Welfare fund. Trussell Trust and Save the Children, 2021 scotland-tackling-child-poverty-and-destitutio.pdf

- FEED. Access to infant formula for babies living in food poverty in the UK: An investigation of the role of food and baby banks. 2020. Date last accessed 20th October Feed+Inquiry+Report+-+FINAL+22.05.03.pdf (squarespace.com)

- Douglas F, Ejebu OZ, Garcia A, MacKenzie F, Whybrow S, McKenzie L, Ludbrook A, Dowler E. The nature and extent of food poverty/insecurity in Scotland. 2015: Glasgow. Date last accessed 20th October 2022. (healthscotland.scot)

- Douglas F, MacIver E, Davis, T, Littlejohn, C. Midwives’, health visitors’, family nurse practitioners’ and women’s experiences of the NHS Grampian’s Financial Inclusion Pathway in practice: a qualitative investigation of early implementation and impact. 2022. Midwives’, health visitors’, family nurse practitioners’ and women’s experiences of the NHS Grampian’s Financial Inclusion Pathway in practice: a qualitative investigation of early implementation and impact. [Report] (worktribe.com)