The latest post in our Nursing Now series shines a spotlight on nursing in remote and rural communities.

Advanced Nurse Practitioner Ian Hall works on the non-doctor Orkney island of Shapinsay while Clare Stiles, NHS Shetland’s team leader for Child Health, oversees the health and wellbeing of children living on 15 different islands. We also focus on community nursing in a large rural patch in South West Scotland by hearing from Senior Charge Nurse Hazel Hamilton.

All three recently became Queen’s Nurses after completing the nine-month development programme.

Ian Hall says he is drawn to extreme remote and rural nursing practice. His last big job saw him help establish the first-ever healthcare and community development project for nomadic Tuareg people, deep in the North Niger desert. These days, he looks after people living on the Orkney island of Shapinsay, and he reckons that there are similarities.

Ian Hall says he is drawn to extreme remote and rural nursing practice. His last big job saw him help establish the first-ever healthcare and community development project for nomadic Tuareg people, deep in the North Niger desert. These days, he looks after people living on the Orkney island of Shapinsay, and he reckons that there are similarities.

“Both communities are resourceful, existing very independently away from the throng,” he says. “They know there are plusses and minuses to that, but it’s their way of life.”

An Advanced Nurse practitioner, able to turn his hand to emergencies, diagnosis, prescribing and treating, Ian is Shapinsay’s resident health professional. Responsible for overseeing the health of the island’s 300 residents, he knows all his neighbours well.

“It’s a fantastic level of relationship which makes treating people easier, but it’s a bit like living in a goldfish bowl,” he says. “It’s obvious who you’re visiting, every move you make is noticed. You know everything about everyone, and have to keep it to yourself. A lot of the islanders are related to each other, so word spreads and trust builds.”

It was Ian’s commitment to developing community nursing in the most isolated places that won him a Queen’s Nurse nomination. “I’m going to use it to promote the kind of nursing I do,” he says. “Being a Queen’s Nurse should give me more clout when it comes to making change happen.”

On Shapinsay, Ian works around the clock, usually two weeks on and two weeks off. When he is not on duty, another nurse practitioner fills in. “That makes it sustainable,” says Ian. “You have to be able to take time off.”

On Shapinsay, Ian works around the clock, usually two weeks on and two weeks off. When he is not on duty, another nurse practitioner fills in. “That makes it sustainable,” says Ian. “You have to be able to take time off.”

Scotland’s small islands have been struggling to recruit and retain health professionals for years. The particular demands of working remotely, often without easy access to clinical support, make it a challenging career choice. There had always been a resident doctor on Shapinsay, until the last one left ten years ago. Despite the Health Board’s best efforts, a permanent replacement could not be found, and for two years, locums plugged the gap.

The Hall family had been visiting friends in Orkney when the nurse-led service had been going for two years. Ian’s wife Jenny saw an advert for an islands nurse practitioner, and he said he would give it a go. Recently returned from Africa, the Halls were working in their native Derbyshire. “But it just wasn’t very exciting, says Ian. “We were looking for our next challenge.”

When Ian got the post on Shapinsay in December 2012, the family bought a working croft on the northern shore, where they raise sheep and goats, hens, ducks, dogs and cats. There were three children, then – twins Jasmine and Alex, now aged 14, and Bethany, who is 12. Their “Orkney blessing”, Thomas, arrived 10 months later. “The children loved it from the get-go,” says Ian. “They have so much freedom to grow.”

Shapinsay, three miles wide and five miles long, has a small harbour, an imposing Victorian castle, and a scattering of cottages and crofts across its fields. The sea glistens azure blue, and on a sunny day it is an idyll. “But in the depths of winter, it’s quite another story,” says Ian. “We have to be able to take care of our own here and be reasonably self-sufficient.”

Shapinsay’s health centre is positioned between the primary school and the community gym. There’s a spacious reception area, a dispensing room, a GP surgery and the nurses’ room, where Ian holds consultations, seeing drop-ins and scheduled appointments.

One of these is John Leslie, known to his friends as ‘Jacko’. He is 66 and needs to lose weight because of Type 2 diabetes. “It’s been building up for years with me paying no attention,” he says. “But I have a very physical job, and I have to keep myself as fit as I can.”

Out all day in his hand-made creel boat, the Mary Jean, Jacko hauls in around 300 kilos of velvet crabs a week, exporting his catch to Spain. “It’s hard work, and I’m glad that I’m able to do it,” he says. “Ian and myself are working to keep it that way.”

On Shapinsay, people with chronic diseases such as diabetes, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are followed up regularly by Ian, and doctors visit from Kirkwall twice a week. “They are very supportive and I can call them at any time,” says Ian. “If I’m faced with a problem outwith my scope of practice I will refer it on, but that’s pretty rare, to be honest.”

Being just a half-hour ferry ride from Kirkwall, Orkney’s capital, Shapinsay is a commuter island and there are many young families who go to work and secondary school there. There are also frail older people, some of whom are housebound. Ian is happy to do home visits, to change dressings, provide catheter care and chat, but there is often a need for home help. “There just aren’t enough carers on the island, and if an older person doesn’t have family here, or they cannot cope, there is very little choice,” he says.

Ian has helped to train people on the island to act as First Aiders and second responders, able to give him support if required. “If there’s a cardiac arrest it takes three of you to deal with it,” he says. “Now there are people I can call on at a moment’s notice.”

In the back of his car he carries his paramedic kit, and he is never more than five minutes away from it. Containing oxygen, gas and air, injectable drugs and a defribillator, this is life-saving stuff. “We’re very well trained here,” says Ian. “We do the Basics Scotland three-day intensive emergency care course every two years, twice the normal requirement. I use it a lot.”

In the back of his car he carries his paramedic kit, and he is never more than five minutes away from it. Containing oxygen, gas and air, injectable drugs and a defribillator, this is life-saving stuff. “We’re very well trained here,” says Ian. “We do the Basics Scotland three-day intensive emergency care course every two years, twice the normal requirement. I use it a lot.”

De-skilling, not seeing enough cases to maintain proficiency across the clinical spectrum, is a risk for remote and rural practitioners. To address that, Ian has started working with the other islands’ nurses to establish a clinical supervision network that they can all use to maintain their knowledge and skills as expert generalists.

When Ian arrived in Orkney, he took part in meetings held by the Isles Network of Care (INOC), a group comprising mainly doctors who came together to discuss issues of mutual interest. Now the isles nurses participate, and there is also a NINOC, the nurses’ version.

There are 10 inhabited Orkney islands which have either Nurse Practitioner or Community Nurse cover. “They are very isolated. When I first came here the nurses rarely got chance to meet,” says Ian. “I introduced the idea of having dedicated time once a month when one clinician could contact another clinician to reflect on their practice. It allows two colleagues to work something through together.”

The nurses use videoconferencing or telephones to link up. “We are developing something new here that could be very useful in other remote and rural settings,” says Ian. “The nurses say it gives them support, and they welcome the chance to talk about case studies and clinical issues they are dealing with.”

Looking to the future, Ian would like to see community nurses’ network continue to develop, and their scope of practice widened to include referral rights: on Orkney, only a GP can order a scan, or request an appointment with a hospital consultant, which means an extra stage in the patient journey. “Confidence is at a good level now,” says Ian. “The patients like the service we give them, and I reckon that having dealt with so much here already, I can deal with most things the island might throw at me.”

By Pennie Taylor

Great Skuas are wheeling high in the sky over Burrafirth beach on the northernmost tip of Unst, itself the most northern of the Shetland Islands. Known locally as Bonxies, these large birds are fierce in their defence of their territory, and will maim and kill if they can. Watching them swoop down to persecute a lone lamb on the hillside below is a reminder that nature is indeed very red in tooth and claw up here at the far top of the British Isles. The people have to be pretty resilient too.

Great Skuas are wheeling high in the sky over Burrafirth beach on the northernmost tip of Unst, itself the most northern of the Shetland Islands. Known locally as Bonxies, these large birds are fierce in their defence of their territory, and will maim and kill if they can. Watching them swoop down to persecute a lone lamb on the hillside below is a reminder that nature is indeed very red in tooth and claw up here at the far top of the British Isles. The people have to be pretty resilient too.

“It’s a long way from a hospital, and we are struggling to recruit doctors at the moment,” says Health Visitor Clare Stiles. “Community nurses are providing the continuity when it comes to health care here.”

Previously a triple duty nurse, Clare has worked as a Midwife, District Nurse and Health Visitor, meaning that she has tended to the needs of the youngest and the oldest, and everyone in between. When she came up from the south to work on the island of Yell 23 years ago, she became the school nurse too. “For me, it was a bit like coming home as I grew up in a little village in the middle of Derbyshire.”

Previously a triple duty nurse, Clare has worked as a Midwife, District Nurse and Health Visitor, meaning that she has tended to the needs of the youngest and the oldest, and everyone in between. When she came up from the south to work on the island of Yell 23 years ago, she became the school nurse too. “For me, it was a bit like coming home as I grew up in a little village in the middle of Derbyshire.”

Some of the islanders on Yell knew who Clare was before she even stepped onshore. “I had delivered the niece of one of the local lads when I was working down in Chichester,” says Clare. ”There was a drink waiting for me at the bar when I arrived.”

As NHS Shetland’s team Leader for Child Health, responsible for managing the team and redesigning how things are done, Clare oversees all the school nurses in Shetland, children’s nurses, health care support workers, and Health Visitors. Together, they look after the health and wellbeing of 1,395 children living on 15 different islands, most of which have primary schools and are served by seven secondaries.

There’s a Hospital Children’s Nurse based in Lerwick’s Gilbert Bain Hospital, and a Community Children’s Nurse who works in the community across the whole of Shetland. The Health visitors are GP-attached and focused on under-5s, and with a healthy birth rate of around 350 deliveries a year, they are kept busy.

As well as managing the service, which she does from an office in Lerwick, Clare maintains her clinical skills by working as a Health Visitor and Practice Teacher on the islands of Yell, Whalsay and Unst. There are 147 under-5s living across these islands, and she is responsible for them all.

Today’s visit is to the family of a newborn in Uyeasound. Emma Ramsay, who also happens to be one of Unst’s GPs, gave birth to daughter Grace three weeks ago in Aberdeen. With Grace’s big brother Thomas and sister Lizzy looking on, Clare weighs the baby, who is putting on the pounds well.

Mum Emma tells Clare that the advice she gave last time, to place salt in the baby’s umbilicus before rinsing with water to help with healing, worked. Emma also expresses surprise that gentle massage can be used to alleviate her baby’s ‘sticky eye’, caused by a blocked tear duct. “I wouldn’t have known that,” says Emma. “It’s Clare’s experience and depth of knowledge that makes all the difference for me.”

Unst is two islands and two ferry crossings away from the Shetland capital, Lerwick. But there are the same social issues as everywhere else –drink, drugs, domestic violence, abuse – and Clare has a significant role when it comes to child protection. Together with social work colleagues, she will assess situations involving vulnerable children, attend case conferences and write court reports. “In such a small place, it can get difficult at times,” she says. “But if everyone keeps the child’s best interests at heart, we can still have a good relationship with the families.”

To improve communication between all the organisations that touch on children’s lives, there are regular multi-agency meetings involving education, health, mental health, social work and the police, where action plans are discussed.

Daily, Clare and her team make contact with GPs, social workers, early years workers and clinical specialists, keeping in touch about children’s care. The nurses practice autonomously, and can refer young patients on directly. “It takes courage to practice the way we do, but we have the training and experience to cope with it, as well as the support of the team and managers,” she says. “We are developing a streamlined service that makes life as easy as possible for families, and we are asking them how things can be improved.”

Clare promotes strengths-based nursing, which supports families to find solutions to problems such as such as a child’s wakefulness at night or bed-wetting. “We help parents to identify their own strengths to help them parent their child,” she says. “That way, they will feel better about dealing with issues themselves.”

At Unst Health Centre, Clare holds a fortnightly child health clinic and catches up with colleagues before going out on home visits. “It’s important that I keep in touch with staff,” she says. “They can tell me whether there have been any concerns or health issues for any of the children.”

At Unst Health Centre, Clare holds a fortnightly child health clinic and catches up with colleagues before going out on home visits. “It’s important that I keep in touch with staff,” she says. “They can tell me whether there have been any concerns or health issues for any of the children.”

“As a practice teacher, I take student health visitors out on clinical placement and tie in theory with practice,” she says. “I love seeing them develop as they go through the stages. They blossom, and it’s wonderful to see.”

She hopes to attract newly qualified nurses back once they have completed their training, and encourages Shetland-based nurses to pursue Heath Visiting as a career. “If we train our own, they tend to stay,” says Clare. “So we act as ambassadors to inspire them.”

Had it not been for terrible stage fright, Clare might have been a classical musician: as a teenager, she won a scholarship for clarinet lessons with the head of wind instruments at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester. She went into nursing instead, but music remains an important part of her life, and she plays clarinet and saxophone with a group of friends in her spare time. “Shetland’s a great place for music and socialising,” she says. “I can’t imagine ever going back to the mainland now.”

Clare and her husband Graham, a care home manager, live on Yell and enjoy taking to the road on their fast motorbikes. They were part of a squad in Brae’s annual Up Helly Aa Viking Festival, and Clare is also vice commodore of her local rowing club, crewing a traditional yoal on the veteran’s rowing team. “It’s very competitive. A few villages own boats and we race each other in all weathers, half a mile out on the open sea,” she says. “That’s a great stress buster after a hard day at work.”

When it comes to her ambitions, it’s simple. “I want our nursing to be excellent. To be the very best it can possibly be, and to make a difference to people’s lives,” says Clare. “Being a Queen’s Nurse is challenging me to think about how I achieve that, and pushing my boundaries creatively.”

By Pennie Taylor

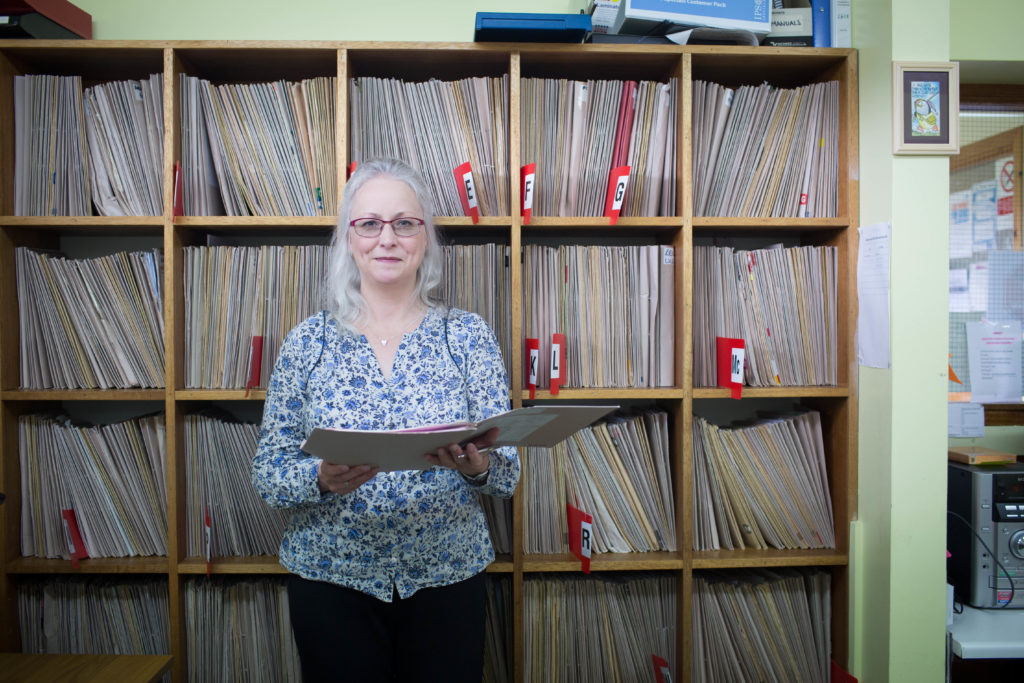

When she took up her post as Senior Charge Nurse for community nursing in Annandale and Eskdale, top of Hazel Hamilton’s to-do list was reorganising the service from a single-practice focus to larger area-based teams.

When she took up her post as Senior Charge Nurse for community nursing in Annandale and Eskdale, top of Hazel Hamilton’s to-do list was reorganising the service from a single-practice focus to larger area-based teams.

Annandale and Eskdale is a large rural patch in South West Scotland with scattered farms, quiet villages and small market towns which are home to more than 38,000 people – most of them elderly. The community nurses provide care for those who cannot make it into a surgery. “If we didn’t go to them, they would be in hospital or long-term care pretty quickly,” says Hazel.

The bulk of the caseload is wound management: post-operative care and leg ulcers, mainly. There is a lot of palliative and end-of-life care, blood samples to be taken, intravenous lines and pleural drains to be managed. “We are doing much more complex work now in people’s homes,” says Gretna-based District Nurse Mary Sherry. “But we are also taking care of the whole person while we are at it, looking out for our patients and their carers to make sure all their needs are met.”

It is that personal touch 70-year-old Linda appreciates most. Housebound for the past eight years in her neat bungalow, she looks forward to the community nurses’ twice-weekly visits to replace the dressings on her swollen legs. “They’re a grand lot of lasses,” she says. “You get used to them and open up to them. They see to my ailments, and we put the world to rights.”

Linda, who has lymphoedema, Type 2 diabetes and a hernia, says she is terrified of going into hospital. “I want to do whatever I can to stay out,” she says. “The nurses help to motivate me. I have lost four stones in weight so far. Next, I want to be able to get out and go shopping.”

Linda, who has lymphoedema, Type 2 diabetes and a hernia, says she is terrified of going into hospital. “I want to do whatever I can to stay out,” she says. “The nurses help to motivate me. I have lost four stones in weight so far. Next, I want to be able to get out and go shopping.”

The community nursing teams – who between them make around 200 home visits a day – are organised across three geographical hubs. Still GP-attached, the nurses can rotate between teams and keep in close touch to familiarise themselves with each other’s caseloads. At weekends, they provide area-wide cover.

There are 30 nurses in total, supported by seven health care assistants who have been trained up to do basic duties such as personal care, venepuncture and simple dressings, and two nurse technicians who keeps track of referrals and knows where everyone is.

Patients have direct numbers to make contact with nurses between appointments if necessary, and home visits are arranged according to their wishes, needs and case complexity. “It’s about being truly person-centred,” says Hazel. “For instance, diabetic patients who need insulin are normally the first people we visit in the morning. We prioritise according to need.”

Mary, one of the service’s three Charge Nurses, describes her manager as “very focused, someone who believes in what she’s doing”. And she credits Hazel’s inclusive management style for making the change process as smooth as it can be. “She works hard to get everyone on board and involve them,” she says. “”Hazel is a role-model, and a great believer in open communication.”

The same qualities earned Hazel a place on the new Queen’s Nursing Institute Scotland (QNIS) community nursing development programme.“It has been such a refreshing and exhilarating experience for me,” she says. “If someone had told me that I would be standing in a circle around a mandala with a group of people I had never met before, feeling the energy, I’d never have believed it. But the Queen’s Nursing teaching has had a big impact on me.”

One of the innovations she has introduced is daily handovers between teams. Linking by videoconferencing, the nurses now discuss cases and share their knowledge. They liaise with the wider multi-disciplinary team when necessary, and keep up-to-date with local voluntary organisations so that they can signpost patients and carers towards other sources of help. “It’s only by working together that we can make sure folk get all the support they need, when they need it,” says Hazel.

After qualifying as a nurse in 1981, Hazel worked in acute medical and coronary care in Dumfries hospital before leaving to have her first child. Married to a dairy farmer, she went back to nursing a couple of years later to work in care homes.

After qualifying as a nurse in 1981, Hazel worked in acute medical and coronary care in Dumfries hospital before leaving to have her first child. Married to a dairy farmer, she went back to nursing a couple of years later to work in care homes.

These days, the bulk of Hazel’s work is focused on balancing the leadership needs of the team and administrative commitments. But she relishes opportunities to get out of the office, and back onto the caring frontline. She enjoys getting hands-on with patients whenever possible, and makes a point of regularly shadowing team members as they perform their clinical duties.

When posts on the team are advertised the community’s nurses’ new role attracts interest, and so far word-of-mouth has been the most effective recruitment tool. “We’ve had a few nurses join us from acute environments on the other side of the border,” says Hazel. “They have brought new skills with them, like intravenous antibiotic administration, that will be really useful to us.”

In an effort to inspire the community nurses of the future, Hazel has organised for third year nursing students from the University of the West of Scotland to work one day a week in a local care home while on their placement.

The first cohort of students developed a project on catheter care, sharing best clinical practice with home care staff, that has resulted in fewer call-outs. The second cohort has just completed a basic guide to skin care for care home workers.

In the Annan community nursing hub, part of the town’s health centre, student nurse Lynne Paul reflects on her community experience. “I didn’t think it would be nearly as busy as it is,” she says. “When I go back into the hospital I’ll have a far better understanding of where I am discharging patients to, and just how much they can do here.”

Hazel sees change as an ongoing process, and actively involves her teams. “It is essential to listen to the staff on the ground, and work collaboratively to influence service development,” she says. “If someone comes up with an idea for improving things, we try it. I tell the team to ‘go with your gut feelings, have courage’. This is a new era for community nursing. The future’s looking good.”

Hazel sees change as an ongoing process, and actively involves her teams. “It is essential to listen to the staff on the ground, and work collaboratively to influence service development,” she says. “If someone comes up with an idea for improving things, we try it. I tell the team to ‘go with your gut feelings, have courage’. This is a new era for community nursing. The future’s looking good.”

By Pennie Taylor

I would be very interested in a position similar to yours and would be grateful if you could advise me of any vacancies in rural areas. I have been working in a GP surgery for the last 2 years and in out of hours, gp locum and a&e depts as a practitioner for 3 years prior to this. Came across you while I was looking for potential opportunities and was green with envy!!!

Hello, I am a 3rd year adult nursing student down here in the West Midlands. I just wanted to say this was an amazing read. I am in awe of the fantastic work that is being done for your patients. Just Brilliant!!!

Hi Naomi, thanks for your comment. We’re Very happy that you enjoyed the blog. We have many blogs written by community nurses about the type of work they do, check them out. Happy reading!